Oasis’s infamous 1997 mad fer it cocaine extravaganza Be Here Now was re-released today, joining last week’s documentary about the band’s early years - Supersonic. Both have generated press, which has got me thinking about the group. I have a lot of time for Oasis, which is fairly easy to get away with. I’m also quite fond of Be Here Now, which is harder to justify. I like it for many of the same reasons I like the band. There’s a mangled innocence about Oasis, and their third album showcases that quite well.

To nip any inadvertent apologetics in the bud: the album isn’t very good. It’s spectacularly not very good. There are the makings of a proper rock record in there, but they’re mostly scattered in rubble. That, however, is its charm. It’s an excess ride. Riding on the crest of an unprecedented popular rise, veins caked thick with drugs, and surrounded by a writhing legion of Yes Men, Oasis produced something profoundly overblown in Be Here Now. The remaster of its lead single, “D’You Know What I Mean?”, sweeps some of the bombastics under the rug, but the video more than makes up for any retroactive modesty:

Glorious, no? Icarus suddenly seems a measured and modest chap. That’s the curiousness of Be Here Now; it’s a Mr. Hyde album, that moment when the demons get the better of the angels and it all gets a bit weird and messy. In that light it’s actually strangely authentic, as well as a fine dirty indulgence. It’s all well and good joining The Velvet Underground in a heroin dream, or going on psychedelic marches with Jefferson Airplane, but what about when things go wrong? What about the monsters? Be Here Now is no Low, to be sure, but it can pass as a decadent cousin. They’re two sides of the same coin.

Spencer Jones, who was responsible for Be Here Now‘s album cover (and plenty of other Britpop artwork), described the photoshoot as ‘Alice in Wonderland meets Apocalypse Now.’ The same rings true for the record in general. It oozes with a sickly mixture of fantasy and horror. By 1997 the fiction of Oasis’s image had engulfed them, and you can hear it. You’re not listening to Oasis on Be Here Now; you’re listening to The Biggest Band in the World. Hearing this again in re-release material reminded me of a 1978 BBC interview of American author Hunter S. Thompson, a man best known for his 1971 novel Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The book’s semi-autobiographical main character, Raoul Duke, became synonymous with Thompson himself, a blend which muddied his character:

‘I’m never sure which one people expect me to be. Very often, they conflict—most often, as a matter of fact. […] I’m leading a normal life and right alongside me there is this myth, and it is growing and mushrooming and getting more and more warped. When I get invited to, say, speak at universities, I’m not sure if they are inviting Duke or Thompson. I’m not sure who to be.’

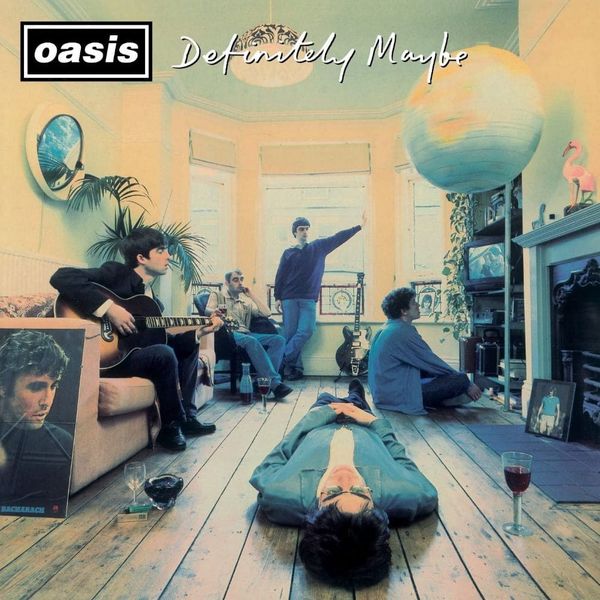

That dynamic of warped and mushrooming myth is unmistakable in Be Here Now. Early Oasis was the stuff of dreams. Working class kids coming out of nowhere with honest, aggressive rock and roll and taken into the hearts of millions. Seeing them go off the deep end carries its own kind of morbid fascination. It makes their early ‘take it or leave it’ brilliance all the more captivating. As Pitchfork‘s Ryan Dombal summarised beautifully in his review of Definitely Maybe’s 2014 reissue, although Oasis ‘were terrible at being The Biggest Band in the World, […] they were amazing at wanting to be.’

In a recent interview with Mat Whitecross, the director of Supersonic, Liam Gallagher says that, ‘What we did in three years took the Beatles eight.’ You can shrug it off as Liam grandstanding, you can argue about quality, but he’s right. The rise and fall between Definitely Maybe and Be Here Now was almost exactly three years. Such a complete story of success, adoration, and implosion took bands like Pink Floyd almost twenty years to achieve. The sound and fury of Oasis’s 1997 burnout is the stuff of proper spectacle, and was in many respects the only appropriate follow-up to (What’s the Story) Morning Glory? Indeed, every album since Be Here Now, for all the standalone hits they boast, has felt like further epilogue to what Oasis achieved between 1994 and 1996.

Be Here Now isn’t important or noteworthy in its own right, but it does hold its own as the Fall portion of the Oasis myth. If you’re looking for something a bit more depraved than cigarettes and alcohol, you might be surprised by just how commanding it can be. I don’t think we ever really tire of seeing people consumed by their monsters, at least in a creative sphere. It makes the highs even more special.