Laina Gould had an eye for talent, an ear for hits, and a nose for the finest cocaine north of Grimsby. These qualities had contributed to a career that had been nothing if not eventful – the bits she could remember at any rate – and a personal fortune that had been nothing if not depleted. She was, as the old saying goes, finished. Washed up. Yesterday’s news. Broke.

For years she had been the record label’s darling, seeking out marketable talent, wooing them into signing contracts they didn’t understand, and making for the nearest exit when they’d realised what had happened. She fully believed in artists finding an audience. She also believed in being paid a healthy percentage of their earnings when it happened. Liam Dowdry & The Dreadful News? That was her. Fio Morden? You bet. Half of Britain’s finest artists were nurtured under Laina Gould’s bleached blonde wing.

Given her own contribution to the music industry’s nastiness, Gould should perhaps have been better prepared to be on the receiving end of it. The label, pressured by shareholders who were ‘deeply concerned’ by her diminishing returns and ballooning expenses, cut her loose.

She had been informed of her dismissal in Coppleton’s phonebox. (The village had one phone box and the villagers were very proud of it.) A particularly wild night of ‘scouting’ had brought her to a nearby bench. When she had called the head office to explain, and request funds for a ticket home, they thought it a fine opportunity to explain her services were no longer needed. They all felt safer knowing she was hundreds of miles away, penniless and with no immediate prospects of enacting revenge.

Her world crumbling, Gould found sanctuary in the village library. After blacking out in the foetal position for most of the afternoon she polished off her medication to clear her head when lo, a fresh opportunity presented itself. Two hapless ‘artists’ wanted a hapless ‘bassist’ to join their so-called ‘band.’ It was like a starving shark smelling blood.

She was now in a booth at the Miners’ Arms scribbling furiously on a napkin while the band members nursed their drinks. Sunshine exchanged glances with Stone and Bas, who had reappeared from their car destroying adventures covered with ash and motor oil. Waltz had introduced himself to Bas at the bar while Gould discussed something with the landlord out of earshot.

The boys sat in silence waiting for Gould to finish writing and address them.

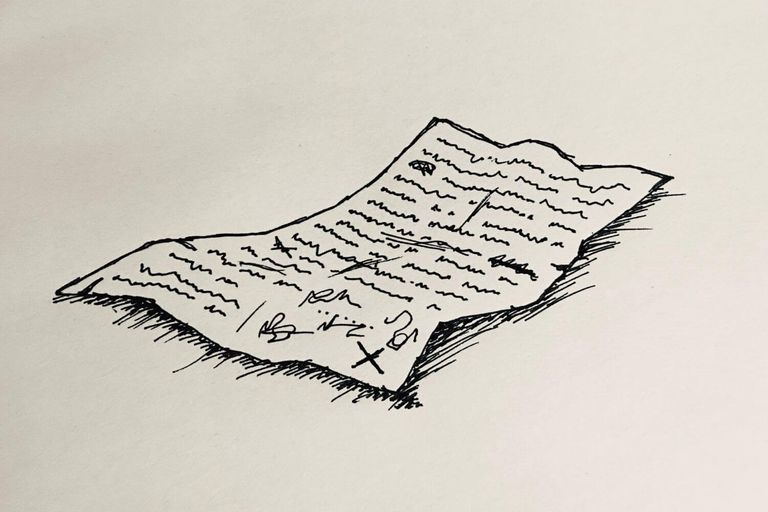

‘Now,’ she duly said, ‘this seems to me like a fair deal.’ With a deft flick she produced a second napkin that had been below the first. Her jagged, slanted handwriting was etched into its surface. A perfect copy.

‘You’ve done this before,’ Hazard said.

‘Nothing gets past you, does it sweetheart.’ Gould patted his cheek. ‘When there’s kismat it’s best to get pen to paper as soon as possible. Someone who wants to sign a contract today may not want to sign it tomorrow.’

Stone’s gargantuan brow crumpled. ‘Why wouldn’t we want to sign this tomorrow?’ he asked.

Gould pressed a hand to her chest in vaudeville shock. ‘Talents like you are bound to be swept up before too long,’ she said, her eyes shining. ‘I believe in what you’re doing and just want to be on board. That’s why I’m asking for such a modest cut of the profits.’

Waltz was holding the second copy of the contract up to the light. ‘What is that cut exactly?’ he said.

‘Ten percent.’

There was a general murmuring of approval.

‘That seems reasonable,’ Hazard said.

‘Per person.’

There was a general pause of disquiet.

‘Which is to say, fifty percent.’

‘Fhdkjah?’ Bas said.

Belatedly, Stone’s mind was shifting from its state of relative calm and finding its way towards apoplectic anger, a condition it was far more comfortable with.

‘Now you wait just a second,’ he said. ‘You want as much as the rest of us combined?’

Gould lit a cigarette and considered this. ‘Yes,’ she said.

Hazard steeled himself to speak. ‘You can’t-’

‘Hey, lady.’ It was the landlord shouting from behind the bar. ‘You can’t smoke in here.’

Gould inhaled deeply, ignoring him. She leaned forward, the glint in her eye giving way to an irresistible darkness. As if under a spell, Hazard, Sunshine, Bas, Stone, and Waltz leaned forward as well. A hush fell over the pub.

‘Now see here,’ she said. ‘You’re an up and coming band with no idea what it’s doing. You don’t know shit about shit. People in this business will take advantage of you. Hell, I’ll take advantage of you, but I promise you this: I will always be honest with you about it. You want to be stars, yes?’

Hazard nodded vigorously. This was enough for Gould, who continued.

‘You’re going to need gigs. You’re going to need radio slots. You’re going to need recording studios and photo shoots. You’re going to need horrible accidents to happen to other up and coming artists that sound like you. I can get you those gigs. I can make those accidents happen. I can fight your corner when you’re passed out on the canvas. Luckily for you, boys, this industry isn’t about how good you are. It’s about how good you are at making people believe how good you are. You don’t want my help? Fine. Walk away. But if you want to make something of yourselves, to play ratty little clubs around the country and maybe, one day, play ratty little festivals, I suggest you sign this napkin, because it’s the best deal you’re ever going to get.’

The band processed this in silence. The landlord, who had approached to reprimand Gould about what was now her second cigarette, backed away and pretended to busy himself at a nearby table. The pub’s decibel levels eased back up to normal.

Bas pulled the napkin towards himself and turned to Gould.

‘Pahldr?’ he said.

‘Of course,’ Gould purred, handing him a pen. Bas signed the napkin – the ink was blood red – and pushed it back into the centre of the table.

‘Well,’ Waltz said slowly, ‘fifty percent of nothing is still nothing.’

Hazard muttered the equation to himself as he mulled it over.

‘That’s true,’ he confirmed.

He and Waltz signed. After a pause, Stone marked an X. They all turned to Sunshine.

‘Don’t fuck this up, Ray,’ Gould growled.

On balance, Sunshine decided it was best for him not to make enemies of his new friends quite so early. He signed. In an instant Gould was up shaking their hands in turn, a picture of joy. Whatever darkness they had glimpsed was gone – for now.

‘I’m so pleased,’ she said. ‘Ever, ever so pleased.’

‘Say.’ Waltz was reading the original copy. ‘What’s this about us being guarantors of your personal debts?’

The napkins disappeared into Gould’s pocket with a whoosh. ‘Don’t worry about that, lovey,’ she said. ‘Standard fine print. Are you ready for your first gig?’

‘You bet,’ Hazard said. ‘When?’

‘Now.’

‘Now?’

Gould nodded at the pub’s empty stage.

‘You’re up.’